The new forums will be named Coin Return (based on the most recent vote)! You can check on the status and timeline of the transition to the new forums here.

The Guiding Principles and New Rules document is now in effect.

[Healthcare & The Elderly] Or, how I stopped worrying and learned to love the Death Panel

Atomika Live fast and get fucked or whateverRegistered User regular

Live fast and get fucked or whateverRegistered User regular

Live fast and get fucked or whateverRegistered User regular

Live fast and get fucked or whateverRegistered User regular

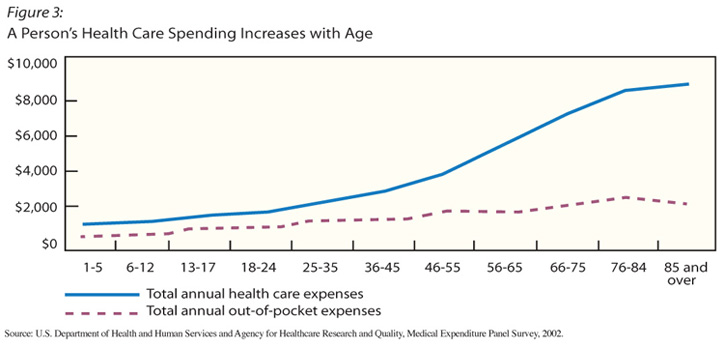

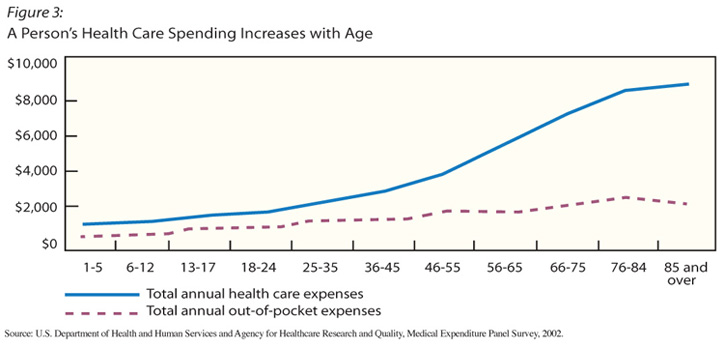

First, some graphs.

As many of you already know, I am a healthcare worker. For a long time before that, I was libertarian capitalist that strongly opposed any nationalization of our healthcare system here in the US. It's funny how spending time getting to understand an argument will inform your thinking on the subject; why, you might even change your opinions on things, once you actually learn what the fuck you're talking about.

The United States, famously, spends a ridiculous amount of money on health care, in both terms of per capita and as a percentage of GDP.

However, looking at the numbers the US does a pretty competitive job in keep the relatively young healthy for a decent cost. Among nation-to-nation discrepancy, our over-expenditure is fairly minimal. Then, look at how we stand against others in terms of elderly care.

So what's up?

I've seen firsthand our approach toward elderly care, and I can tell you, it's radically broken. And it's not the doctor's fault, or the hospital's fault, or the industry's fault (though they do all get some blame); rather, I feel it's largely the American culture's fault and failing in that we collectively cannot actualize death and dying, or the fact that we don't seem to accept that it will happen to us all.

Case in point, when a 85-year old patient with terminal lung cancer arrives to the Emergency Room in cardiac arrest, they will receive the same treatment given to a 40-year old with no health problems in cardiac arrest. Then, should that 85-year old patient continue to do poorly, they will be given CPR, put on a combination of electrical contractility agents and vasopressors, and probably mechanically ventilated before they are taken up to ICU, where they will likely die in the next day or so.

This is protocol, but more importantly, this is the law. EMTALA, the legislation that controls emergency practice at any hospital in the US that accepts Medicare and Medicaid, states that unless otherwise stated, in an emergency in which your life or ability is immediately threatened, the hospital is legally obliged to perform any and all medical procedures in an attempt to keep you from death or disability. Of course, if you have a living will with a directive that instructs against that, the hospital won't do anything; however, your paperwork better be on-hand or on-file when you show up, because hospitals do not accept verbal Do Not Resuscitate orders, and will continue with life-saving measures until proof is shown to direct them otherwise.

So of course the question becomes, how do we combat this profound disparity of spending? Do we mandate end-of-life agreements for all people? Do we institute authorities within institutions that can terminate care against the wishes of patients or their families? Do we take the decisions out of the hands of the patients and families entirely? After all, as the situation stands now the next-of-kin can order the hospital (and through this, Medicare and the tax dollars it's funded by) to spend an infinite amount of money on measures until the patient recovers or expires.

The short argument is, are we getting a reasonable return on our massive expenditure of keeping the elderly around, and if not, what's the plan to correct this?

As many of you already know, I am a healthcare worker. For a long time before that, I was libertarian capitalist that strongly opposed any nationalization of our healthcare system here in the US. It's funny how spending time getting to understand an argument will inform your thinking on the subject; why, you might even change your opinions on things, once you actually learn what the fuck you're talking about.

The United States, famously, spends a ridiculous amount of money on health care, in both terms of per capita and as a percentage of GDP.

However, looking at the numbers the US does a pretty competitive job in keep the relatively young healthy for a decent cost. Among nation-to-nation discrepancy, our over-expenditure is fairly minimal. Then, look at how we stand against others in terms of elderly care.

So what's up?

I've seen firsthand our approach toward elderly care, and I can tell you, it's radically broken. And it's not the doctor's fault, or the hospital's fault, or the industry's fault (though they do all get some blame); rather, I feel it's largely the American culture's fault and failing in that we collectively cannot actualize death and dying, or the fact that we don't seem to accept that it will happen to us all.

Case in point, when a 85-year old patient with terminal lung cancer arrives to the Emergency Room in cardiac arrest, they will receive the same treatment given to a 40-year old with no health problems in cardiac arrest. Then, should that 85-year old patient continue to do poorly, they will be given CPR, put on a combination of electrical contractility agents and vasopressors, and probably mechanically ventilated before they are taken up to ICU, where they will likely die in the next day or so.

This is protocol, but more importantly, this is the law. EMTALA, the legislation that controls emergency practice at any hospital in the US that accepts Medicare and Medicaid, states that unless otherwise stated, in an emergency in which your life or ability is immediately threatened, the hospital is legally obliged to perform any and all medical procedures in an attempt to keep you from death or disability. Of course, if you have a living will with a directive that instructs against that, the hospital won't do anything; however, your paperwork better be on-hand or on-file when you show up, because hospitals do not accept verbal Do Not Resuscitate orders, and will continue with life-saving measures until proof is shown to direct them otherwise.

So of course the question becomes, how do we combat this profound disparity of spending? Do we mandate end-of-life agreements for all people? Do we institute authorities within institutions that can terminate care against the wishes of patients or their families? Do we take the decisions out of the hands of the patients and families entirely? After all, as the situation stands now the next-of-kin can order the hospital (and through this, Medicare and the tax dollars it's funded by) to spend an infinite amount of money on measures until the patient recovers or expires.

The short argument is, are we getting a reasonable return on our massive expenditure of keeping the elderly around, and if not, what's the plan to correct this?

Atomika on

0

Posts

I think (and I know this sounds like a cop-out) that it should be decided on a case-by-case basis with metrics dependent on things like:

- expected compliance with routine

- lifestyle habits

- expected outcome

- comorbidity factors

An active 70 year old who lost a kidney or two to an acute illness would definitely get priority care over the 70 year old who was morbidly obese and smoked 2 packs a day.

Regardless, I think a key to preventing either case is mandating routine annual physical exams for everyone over 45. So much of the illness I see in hospitals is preventable, but often the patients have gone years without even a cursory exam and live terrible lifestyles. I'm not shocked when it turns out the old guy who smells like a tannery tells me "I hate doctors," nor am I shocked to find out his shortness of breath is caused by lung cancer.

I'm wondering if we shouldn't bump people from therapy for people who did do this but we're out of space or resources.

Like say we used to have a surplus, and the 80 year old man who was non-compliant, suddenly we need his space, I honestly think we should get to bump him for the new person who is compliant.

But wouldn't changing that open the can of worms that is assisted suicide?

The problem is that the moralistic arguments for elderly care cannot exist in a world of limited resources. The question of when to restrict care cannot be answered by humanism or self-interest, because we will always choose life over death. Even if that life will be short, ugly, and full of misery.

And that's how I an tell you work in a hospital and deal with lots of old people.

Change isn't a binary value.

And assisted suicide doesn't have a lot of strong arguments against its viability. I'm a big supporter of assisted suicide (in cases of terminal illness/pain), and you'll be hardpressed to find a healthcare worker who doesn't already have a contingency in mind for such a situation, should they need it.

There was a really good interview on NPR a week or two ago about hospice care.

Apparently, to get Medicare to cover hospice, you have to sign something saying essentially "I am dying and I am no longer trying to fight my illness."

So a lot of people don't do it an end up in more expensive and less comfortable situations on their way out

I think it's more a "weak faith" thing. I can't tell you the number of people I've known who quit being Christian when they were young because their 83-year-old grandma ended up in the hospital with lung cancer, they prayed real hard, but in the end she died anyway. Apparently the fact that she died quietly when asleep instead of gasping away clawing at an oxygen mask doesn't matter; no, she needed to throw off the blankets Lazarus style and live for another forty years (and maybe have another kid like Abraham's wife supposedly did) for it to count.

That's one thing that's always weirded me out: how we went from a world where just a century ago death was a common and accepted part of life to one just egregiously scared of it ever ending, not matter how poorly it is. It's obviously related to how we've become psychotically youth obsessed, but I can't pinpoint exactly when the switch got flipped.

What bothers me about what Ross writes is that we have this obsession with life extension no matter the cost, but at a certain point you really need to take into consideration quality of life over quantity of it.

You show a lot of statistics which show that you have a radically broken healthcare system, in which the average cost per person is the highest in the world, while the care received does not seem to warrant that. You then draw the conclusion that the problem is in the elderly, and that the system is ok in other age groups. I for one don't see that in the numbers quoted. Your numbers could (and in my mind do) show that across ALL age groups the US system is causing over-spending for very little returns.

You then propose the following solutions:

Do we mandate end-of-life agreements for all people?

Do we institute authorities within institutions that can terminate care against the wishes of patients or their families?

Do we take the decisions out of the hands of the patients and families entirely?

NONE of these are even remotely considered in ANY of the civilized countries that are lower than the US on the healthcare expenditure list. Funnily enough, just having an option of well-cared for euthanasia does achieve some cost reduction as a side-effect, but framing that debate in THIS light is abhorrent. This is the kind of thinking that leads idiots to say that in the Netherlands people are being euthanised against their will.

Look at Japan: Lowest on your list, HIGHEST life expectancy in the WORLD. This country is NOT mandating sepukku for its elderly, NOR withholding care above a certain age.

As a matter of fact, NOT ONE of the countries on your comparison list is BELOW the US in terms of life expectancy. Source

Please, please, please look elsewhere for reducing your health care costs. First and foremost, I'll give you a hint: almost NONE (and I'd even wager, NONE AT ALL) of those countries does NOT have single payer health care. Results speak for themselves, even to those who choose to ignore them.

There's two ways of looking at this: you're paying top dollar for third-rate care. You could reduce the care given to a certain section of the populace even further. Do you think THAT would solve it?

I assume "we" = the United States, and "you" = a person making end-of-life decisions.

Some more recent numbers: http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/10/14/us-care-costs-idUSTRE69C3KY20101014

the "no true scotch man" fallacy.

I think it your example case change is pretty binary. If you don't give that 85 year old CPR, he dies.

And I am not saying assisted suicide is wrong, but it will inevitably be drawn into the discussion once you are trying to change the law regarding that 85 year old terminally ill patient. Besides, in your example it is pretty clear that giving that patient CPR and doing everything to extend his life is a waste of money. But where do you draw the line? And what factor makes you decide that CPR isn't necessary? That he is 85 years old? That he has terminal cancer? Both? So what happens with somebody who is 40 but hast terminal cancer? And maybe his death wouldn't be a day away but a year or five years? What do you do with a relatively fit 85 year old, that doesn't have lung cancer, but might keel over due to old age a month later?

But ultimately, yeah, you are right. This is more of a cultural issue than purely a "how should we cut costs" issue. A simple "here are the criteria for when we can let people die" probably won't help.

Who is the 'we' in this sentence?

Effectively, demand for end-of-life care is astronomically high. This means that adding to the supply - building more hospitals, adding beds, hiring doctors - will just result in more end-of-life utilization, without necessary improving the quality of care.

There seem to be a lot of factors driving this, but mostly... it's the patients: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/27/national/27death.html

There are other issues as well. Poor coordination of care means that you might be told, "there's nothing we can do for your family member" by somebody who you've never met, who has spent maybe 10 minutes talking to you, and who will disappear after the conversation. This, in turn, is driven by insurance billing rates that push physicians to see more patients and spend less time with them. EMTALA is a factor, as Ross pointed out, which can be mitigated by 'medical futility' laws - state laws that protect physicians who refuse treatment deemed futile.

the "no true scotch man" fallacy.

Yes. Exactly. This is exactly what we do.

Physicians aren't servants. They are not morally required nor should they be legally or financially required to provide every imaginable service under the sun regardless of cost or predicted outcome.

Nope. You're flatly wrong here. In every country with universal health care, there are authorities - physicians, hospitals, or reimbursers - who have the power to withhold care if the prognosis is poor. The US is the only country (to my knowledge) that broadly incentivizes futile care.

the "no true scotch man" fallacy.

An example: I just got prescribed antibiotics yesterday. I didn't have to pay a penny for them because I have awesome-sauce insurance, but the doc prescribed Omnicef for me. The generic for omnicef (which is what I got) is about $5 per pill, so that's a $100 bottle of pills. I don't have a history of amoxicillin-resistant bacteria or anything, and amoxicillin costs about an order of magnitude less.

Last year I had to take an ambulance ride to the hospital when I had a mishap with a power tool and was bleeding too badly to drive myself to the hospital. Again, I didn't have to pay for it, but the bill would have been upward of $4000 for the ride to the hospital, a shot of morphine, two x-rays, and ten or so stitches. About $800 of that was a 5 mile ambulance ride. I know that hospitals are forced to increase costs to cover the many ways that they're gouged by insurance providers and medical supply manufacturers, but, again, I feel like cutting the prices at the bottom where the hospitals are gouged and, thereby, eliminating the need to gouge patients would do more for decreasing overall medical care spending in the US than would eliminating required treatments for the elderly.

That's all well and good, but places like FOX will vilify you for the commie liberal hippie you are trying to destroy the capitalistic infrastructure and there you go. Part of fixing this would be first wresting away the control of talking points from the plutocracy but that's an order of magnitude that would help the world and will never be allowed to occur as long as we can pepper spray pregnant women and grandmas into submission.

I'd be very interested in learning about Japan's data and public policy w/r/t annual preventative care and comorbidity factors.

This is merely speculation based on my time in practice, but I have a strong suspicion that one of the reasons the US spends so much on healthcare is that America is actually much, much sicker than the rest of the world, and certainly in terms of preventable (and costly) diseases.

(diabetes rates below)

Aside from McDonald's ham"burgers" and Starbucks milkshakes, would you attribute a part of this to how many Americans are overworked and never have time/resources for vacations, etc. (meaning that the stress from being worked to death, always worrying over making ends meet, et al, can't be good for us)?

Hospital bills are artificially inflated because of the insurance negotiation process (among many other reasons).

Let's say a procedure costs them $2000. They want to make a little extra either as profit or to cover the indigent, so their target reimbursement is $2500. Well, every 1-5 years, the hospital network negotiates its reimbursement rates with the insurance companies. If they actually publish the charge for that billing code as $2000, the insurance companies might say, "Oh, well, we'll pay 45% of that - $900." Then the hospital has to negotiate up from $900.

Instead, by putting the charge down on paper as $4000, they can high-ball the insurance companies, and the starting point for negotiation is more like $1800 - a much more reasonable figure.

But since they're using the same billing schedule for all patients - insured, uninsured, Medicare, indigent, whatever - everybody gets billed $4000.

That's why uninsured patients can often call up hospitals and have them simply forgive huge chunks of a bill. Since the procedure's cost was closer to $2k, the hospital can just say, "Oh, well, we'll take $2k off of your bill for you. Just pay the rest."

the "no true scotch man" fallacy.

I'm not sure. I don't have the data to back up any assertions I might make. I suspect this is likely true for lower-income laborers who are either working long hours or multiple jobs to make ends meet, but at the same time I don't think it's likely for middle/upper-income earners on the same scale.

Now, poor healthcare disproportionate affects the lower-income brackets more strongly, so there could be some correlation, I grant you. However, I think the primary reason behind our collective ill-health is that we consume a diet that is grossly incompatible with the lifestyle of the regular American. I'd guess the average adult American that regularly eats out at restaurants and buys coffees and drinks energy drinks consumes somewhere between 3000 and 5000 calories daily. It's actually isn't that hard to do; a single combo meal at a fast food restaurant will get you 1500-2500 calories with little effort, and it's no work at all to put that number over 3000- for just a single meal. The average adult probably only needs 1800-2000 calories DAILY to maintain their BMI, and most of that needs to come from fruits and vegetables; most restaurant and fast-food meals tend to be very carbohydrate, fat, and protein heavy, the least things you need.

Add into that the basic and widespread cultural notion of self-determination and "it's a free country so I'll damn well be whatever I wanna do," and that's how you get a nation of people who eat like shit and smoke all day and will tell you to your face how much they hate doctors.

Right. I understand that the hospital isn't gouging patients in order to line their purse. I'm saying that tackling the root of the cost issue - in the case of hospital bills, the insurance providers - would be more effective than tackling it from the top down by changing what kinds of care are offered to which people. As pointed out in a couple of posts up-thread, the medical costs in the US are like 2.5 times higher and rising past age 45 as compared to other nations. I don't think we're offering 250% more care than hospitals in Japan or the UK, and while offering less overpriced care would lower the per-person elderly-care expenses, I don't think it would do it in a particularly useful manner.

This is basically the long and short of it. It's an endless demand for a product that virtually doesn't exist. With things like EMTALA and the amount of liability most doctors and hospitals take on, there's no cost curve that consumers have to work with, because for one, government entitlement programs are typically footing the bill, and for another, almost everyone chooses "life" over "not life," even if the result will be poor. The economic intersect graph is just one straight line pointing upward and outward; since there is no real and immediate cost to the consumer, they will take as much "life" as they can get.

Twitch Stream

That culture has to be the biggest problem. On a practical level, I really do like the idea of mandating annual check-ups (presuming they could be covered by the government, if need be), and it could potentially help save scores of lives and save enormously on resources by way of preventative care, but it's for this reason that I really have a hard time believing such a thing could ever make it through government in this country.

It's a close parallel to the supreme court health care debate. This issue, debated among the public, would almost certainly be defined by a fundamental confusion as to how the individual's behavior can and will ultimately effect his or her entire community. "But I don't want to see a doctor and it's my health, dammit!"

That attitude alone would probably bankrupt any socialized medical system implemented in this country.

Oh, Christ, so do I. She probably set the palliative/hospice care movement back 20 years with her horseshit.

But it's not like Palin is a rogue agent, saying things no one else is thinking. A huge portion of people, especially evangelicals on both sides of the ballot, don't believe in right-to-die or hospice care because it's "playing God." To them, whenever they enter one of my hospitals, I always want to point out that God is apparently trying to kill them already and they've come to my hospital to keep His will from being imposed.

As for me, if I'm a patient needing emergency medicine, fuck yes I want my doctor to play God. Obviously the real God has it in for me. I can't tell you how many 75lb 100-year olds who were in PVS that I've done full codes on at the family's insistence, though. It's a large number.

It's in the same family of arguments as those that fail to account for public infrastructure when they bemoan taxes.

I've always held the strong belief that people should be free to utterly destroy themselves, just as long as they don't expect anyone else to do anything about it. You start to see people obese people routinely choose bad food over diabetes medication, or emphysematics choose 3 packs a day over their blood pressure meds, and you lose that compassionate edge.

The second you dial 911, you've lost your Objectivist cred.

Are you familiar with the QALY system?

Formalised system for making these kinds of decisions.

I am (my undergrad is in International/Healthcare Economics), and I like its utilization in theory, but it's got some holes in it. For one, most traditional models view health on a binary scale of either "well" or "dead" and all values fall between those two outcomes. The big thing we're arguing here is whether or not "dead" is the worst value on that scale, to which I'd argue a vehement disagreement.

From the example Bowen and I used above, kidney dialysis is actually a terrible value in terms of adding quality to remaining years or extending life, because so many people who are on dialysis typically have many other comorbidities that prevent them from really gaining significant utilization from the therapy, and because the cost of the therapy is so outrageously high (about $80,000/yr). As well, prognosis for many patients on dialysis isn't typically more than a few years, regardless of their age when they start the therapy. Much like chemotherapy, dialysis fucks your body up as much as it helps; it's a bit of a slow death sentence, since without it you'll die pretty much immediately (within a week or two), but with it you'll still likely die in a few years.

I've been thinking it through this whole thread, and I sense you've maybe missed the problem - it's not that palliative care is bad or that people hate it, it's that many people believe a panel of cost-focused bureaucrats shouldn't be the ones deciding. I know someone will mention that this already happens with insurance, but there is a difference between "I cannot afford to extend life" and "I am not allowed to extend life".

How else are people supposed to respond to statements like Feral's? Or more specifically, are you terribly surprised that when you put the issue in stark terms, people react just as they did to the death panel accusation?

No, they aren't different.

Because no one has said "you aren't allowed to extend life", they've said "We won't pay for it". Which, yet again, makes it about whether you can afford it or not.

Everytime someone talks about terminating care, what they are talking about is terminating payment for care.