The Coin Return Foundational Fundraiser is here! Please donate!

Solzhenitsyn dead!

saggio Registered User regular

Registered User regular

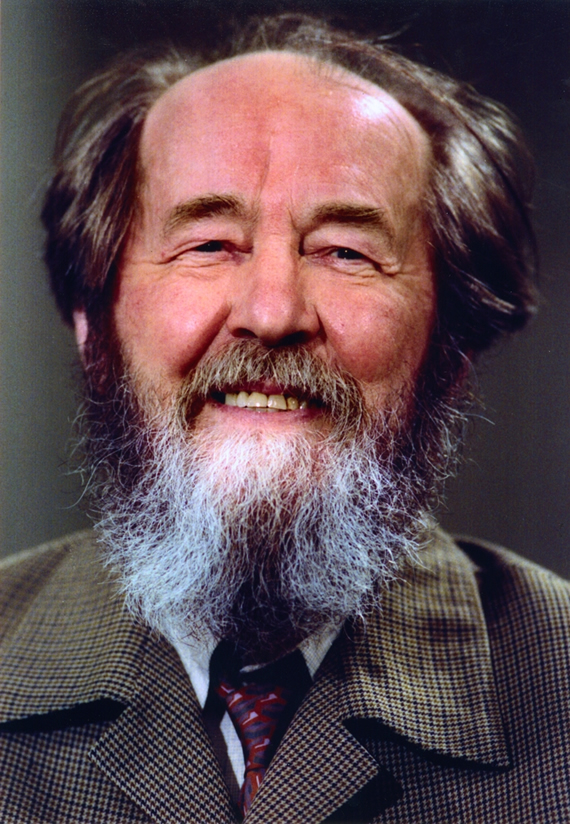

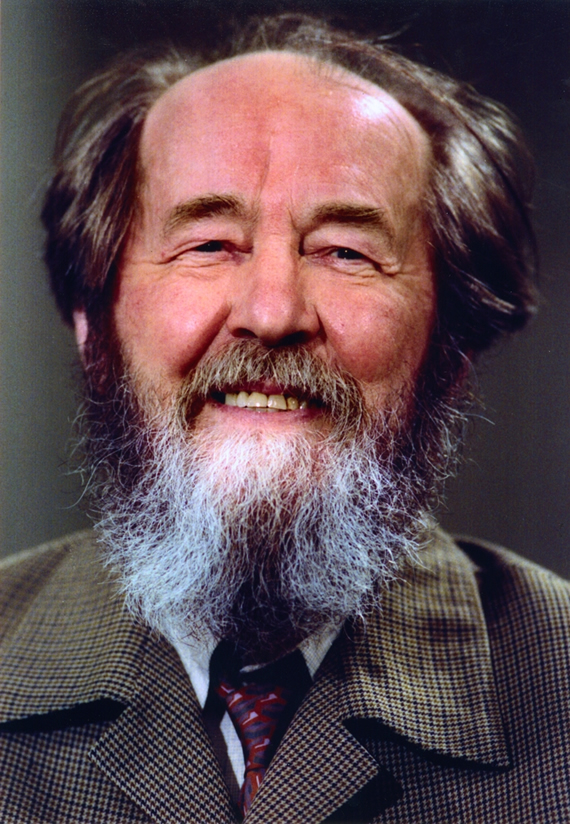

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn dead at 89

I really can't believe this, but the greatest Russian novelist and dissident of the 20th century died Sunday, at the ripe old age of 89. He wrote some of the most amazing Soviet-era literature, the most famous of his works being The Gulag Archipeligo and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich - both works which were highly critical of the Soviet regime. He himself spent a number of years as a political prisoner in exile in the Siberia gulag:

But he was eventually released, and was able to continue with his writing. In 1970, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in 1974, he was expelled from the Soviet Union for writing The Gulag Archipeligo. He would only return to Russia after the end of the USSR and fall of Communism in Europe, in 1994.

Links: http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5jeVYeBxHYWfaTLJPs3J48Jt8bbdQ

http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5hOCBXp8R4DbXpx4cbI_oHOomRX3wD92BIS380

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/24c7f888-6238-11dd-9ff9-000077b07658,dwp_uuid=70662e7c-3027-11da-ba9f-00000e2511c8.html

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/7540821.stm

http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/08/solzhenitsyns_literary_legacy.html

Posters of D&D, what do you all think of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn?

I really can't believe this, but the greatest Russian novelist and dissident of the 20th century died Sunday, at the ripe old age of 89. He wrote some of the most amazing Soviet-era literature, the most famous of his works being The Gulag Archipeligo and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich - both works which were highly critical of the Soviet regime. He himself spent a number of years as a political prisoner in exile in the Siberia gulag:

But he was eventually released, and was able to continue with his writing. In 1970, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in 1974, he was expelled from the Soviet Union for writing The Gulag Archipeligo. He would only return to Russia after the end of the USSR and fall of Communism in Europe, in 1994.

Links: http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5jeVYeBxHYWfaTLJPs3J48Jt8bbdQ

http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5hOCBXp8R4DbXpx4cbI_oHOomRX3wD92BIS380

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/24c7f888-6238-11dd-9ff9-000077b07658,dwp_uuid=70662e7c-3027-11da-ba9f-00000e2511c8.html

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/7540821.stm

http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/08/solzhenitsyns_literary_legacy.html

Posters of D&D, what do you all think of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn?

3DS: 0232-9436-6893

saggio on

0

Posts

hey, why the long face?

(too soon?)

but seriously, I am sad that he's gone. He was definitely a great writer.

Never? Really? That's quite unfortunate. Many consider him the greatest Russian novelist of the 20th Century. The saying goes that the Tsar had Tolstoy and that Stalin had Solzhenitsyn. The guy was just amazing in just about everyway. Except for his strident nationalism after his exile.

There's a story of how there was a warrant out for Solzhenitsyn, and the KGB were looking for him - but he had sought refuge in Rostropovich's house. Now Rostropovich was of course a very famous cello virtuoso, and no one from the KGB would dare enter his house or do anything to him. His celebrity protected him in a big way. So, with Rostropovich at the front door berating the KGB agents for disturbing his privacy and practice time, Solzhenitsyn was in the kitchen finishing the manuscript for The Gulag Archipeligo. Which was then published internationally, and then smuggled back into the Soviet Union in fake cans of paint and boxes of soap.

I think my brother killed him, by the way. He read One Day in the Life... and on the day he finished it Solzehnitsyn died.

The Gulag Archipelago is about three volumes, is non-fiction, and is depressing and powerful as hell. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is short, easy to read fiction that gives you a brief but accurate glimpse into the life of a political prisoner in Siberia. I'd start with that one.

Then maybe Cancer Ward. Which is another great one by ol' Alexandr, but isn't as expansive or as hard to read as the Archipelago.

It's pretty much the only book where I've laughed when I should be crying. Way too often it's surreal.

I read "Архипелаг ГУЛАГ" first and I didn't enjoy his two other novels as much as it.

same, but it managed to get through the wall of ignorance I had around me for so many books in high school. I really liked that one. It was, ya know... good.

I remember reading this in grade 9 or so, and only read through it the once but I still remember the general jist of the day/story. I know you can't parallel your current life to what the character went through but if you ever thought about some of your worst days compared to what happened in this book you'd feel a bit of guilt for thinking how bad you had it. I didn't even realize that this was the author when I clicked the link but remember the novel fairly well even 15ish years later. From what I recall from 15 years ago, I highly recommend this novel.

As for the author, dead at 89, sure most of us hope we make it that long in our lives.